To What Extent Is Objectivity Possible in the Production or Acquisition of Knowledge?

Paulina Suchecka

Volume I - Issue I

October 7, 2024

This exhibition debates the extent to which objectivity is possible in the production or acquisition of knowledge based on the theme ‘Knowledge & Politics’.

This exhibition debates the extent to which objectivity is possible in the production or acquisition of knowledge based on the theme ‘Knowledge & Politics’. Researching the topic, I found three definitions of objectivity that diversify the perspectives of inquiry and used each in one commentary.

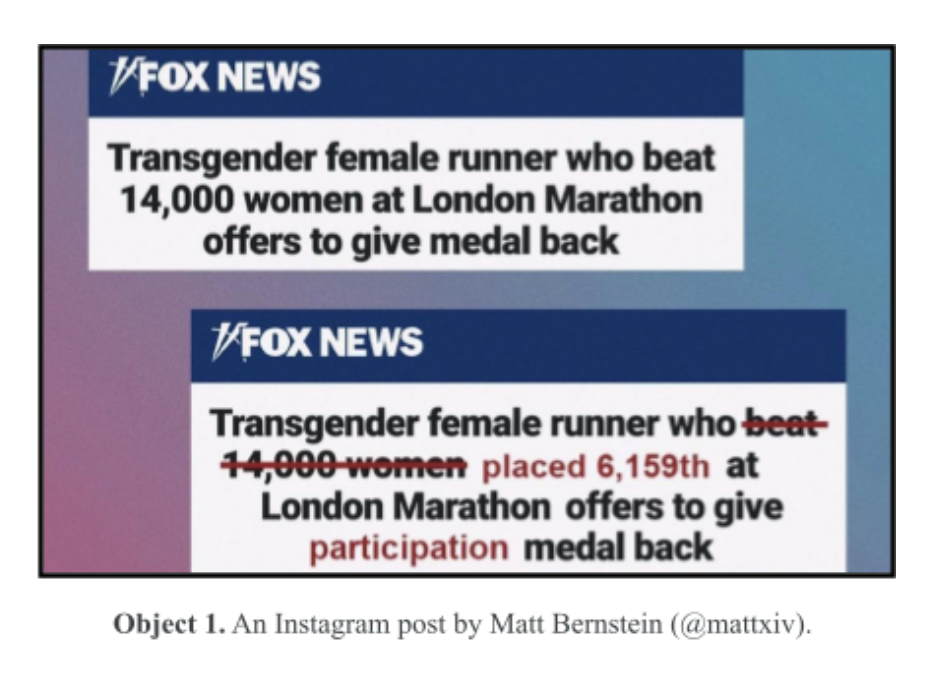

Object 1 discusses the question ‘how unlikely is objectivity in the media?’. Object 1 is a post I found on my Instagram Explore page fact-checking Fox News media coverage of the 2023 London Marathon. I was shocked by differences in these two narratives, particularly the role of a transgender athlete as the villain in one and the victim in the other.

The news is a source of knowledge whose function is to provide objective facts. Considering the bias evident from this object, knowledge produced by news lacks objectivity, specifically due to the ideological agenda of the outlet. Thus objectivity, as ‘independence from particular (...) perspectives and preferences’, is unlikely in the production of knowledge in news because of embedded ideologies (‘objectivity’).

Noam Chomsky argues that the content of knowledge produced by private news media depends on economic calculation; to best monetize the audience, media outlets filter news through 5 filters: ownership, advertising, sources, flak and the common enemy (Al Jazeera). The common enemy filter discourages news producers from maintaining objectivity due to the possibility of generating a unified, easily monetized audience. The common enemy filter strives to put a certain person or group in a negative light to coalesce the audience in opposition to the ‘othered’ worldview, e.g. a transgender athlete. The worldview propagated by the produced knowledge aligns with the preferences of the media outlet owners. News may compel audiences to fear the common enemy through misinformation evoking a sense of injustice, as object 1 does. Emotive news language makes audiences unlikely to identify with the ostracized group. Previously varied worldviews among viewers become homogeneous. This is profitable for news agencies because it solidifies viewership through common identity and allows media owners to profit more by selling a highly homogenous target audience to the advertisers (‘target audience’). Therefore the common enemy filter not only creates a sense of community within the audience but also links back to the advertising filter. Given object 1 and the related question, objectivity in the production of knowledge by news outlets is unlikely because it is economically unporfitable.

Object 2 poses the question: ‘how does agenda-setting power impact objectivity?’. This is a picture of a Geography student and a TOK student posing with a poster of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) from my TOK classroom. The SDGs were unanimously accepted by the UN as objectives for global development. Considering the varying goals of actors, the ‘universal’ objectives were shaped by the subjective preferences of the powerful (Abebe, Daniel).

The subjective process of codifying the SDGs evokes agenda-setting power. This category of soft power allows actors with legitimate authority to establish the values, rules and goals (Watson and Hill). Objectivity, as ‘not favoring a particular group’, is disrupted when agenda-setting power is in place (‘Objectivity’). By the definition of power, groups achieve their goals by bending others to their will (Murphy and Gleek). Therefore to ensure the execution of the main objectives, less powerful groups tend to compromise on the most meaningful goals and use their joint power to dictate the agenda as the most powerful actor. The initial imbalance of power between groups leads to some having more say in the common agenda, breaking the definition of objectivity. Therefore the supposedly ‘universal’ goals are subjective products of imbalance of power.

From a consequentialist standpoint, this lack of objectivity is both likely and beneficial because it yields the greatest good to a wide, heterogenous group by increasing the capability to execute main objectives. In the case of SDGs, the goals are shaped by agenda-setting power of the great powers but reflect global needs. If cooperation for a common agenda was balanced, subversive cultures could jeopardize the SDGs.

Given the argument, the object enriches the exhibition by outlining the benefits to knowledge acquirers brought about by a compromise on knowledge produced by agenda-setting.

Object 3, which is my school's student handbook, is relevant to this prompt as it asks the question ‘how is objectivity manufactured in education?’. The handbook was written according to the school’s intended common worldview as set by actors with agenda-setting power: the administration.

However, in an international school, the presence of objective right and wrongs bring into question the issue of varying cultures and values.

While the majority of rules like academic honesty are universally agreed upon because they are principles reinforced by the agenda-setters in all epistemic communities, there are some values which are more controversial among students of different cultures as the 'objectivity' being enforced negates the subjective nature of such knowledge . For instance, some students quote their cultures to dispute matters like abstinence. Thus controversial rules by the above definition could not be objective.

Schools intend to unify the worldview by invalidating subjective interpretations. Applying Gramsci’s theory, the reward and punishment system is deployed to persuade students to act within guidelines. The dominant education system artificially unifies the opinion, making subjective decisions of the school owner appear objective. This process helps to explain how the agenda-setting power of schools manufactures consent regarding rules.

Education systems rely on teaching facts. ‘Facts’ taught at schools under the coercive power of punishments from handbooks are oversimplified or manipulated to appear objective. The objectivity of knowledge taught at schools is blurred by its goal to persuade students to agree with the promoted manner of behavior or worldview.

Overall, objectivity at schools is likely because it is manufactured by coercive power and indoctrination to become the ‘common worldview’.